Here we are, at the close of another year. School has

finished. Some will be beginning to take holidays. And of course, Christmas with its symbology, liturgy, and doxology are all around us. Santa is available for

photos in the shops, carols are on the radio, and trees and lights fill the

city. And it fascinates me the amount of energy and money are invested into

what is considered traditionally to be a religious holiday, even by secular

society. Currently I am reading Mark Sayers’ book, ‘The Road Trip that Changed

the World’, and in it he discusses how the emergence of a secular society has

marginalised the transcendent, choosing to focus more on the immanent. Choosing

to find ultimate meaning and purpose in the here and now in things like work,

science, and pleasure. Yet, within all of us is a yearning for the transcendent.

As C.S. Lewis wrote in Mere Christianity, “If we find ourselves with a desire

that nothing in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that

we were made for another world.” And perhaps this is the reason why the atheist

enjoys Christmas. Maybe, as much as they may reject Christianity, the themes of

hope, love, giving, and togetherness which are found in the story of the birth

of Jesus, even if in their mind is based on a fairy-tale, is touching a deep

longing within them. And this yearning after transcendent is rooted in the

desire to worship God, an ‘impulse’ wired into our DNA by our creator, albeit

twisted by sin. And this desire truly comes alive and is straightened when one

comes to faith in Christ. And this, it seems, is the fuel for the origins of

Christmas.

Last year, (exactly a year by coincidence) I wrote about

the history of Christmas (here),

to discover its origins and ask, is it a pagan holiday and should Christians

celebrate it? And what I found was that, although there are some parallels

between the Roman Saturnalia and the Scandinavian Yule, the relationship in

iconography is quite weak and most likely coincidental/accidental, and any

claim that Christmas is a contextualised pagan holiday is speculation. This

year, I want to consider why the Church established Christmas from another

perspective.

As part of my post on Christmas last year, I looked at

the development of dates and how there appears to be no calculations for dating

the birth of Jesus until the late second century, and December 25th

does not appear until the fourth century. However, since then I have found

evidence that suggests a December date was proposed by Hippolytus around the

early third century (the originality of this is debated). Nonetheless, the

truth is the early church did not know and relied on philosophical reasoning to

calculate the birth of Christ. Within these Christians was a desire to honour

Jesus by celebrating his birth. And this was quite unique as Jews, the early church's predecessor generally “did not celebrate their birthdays. Indeed, while the dates of

passing (yahrtzeit) of the great figures of Jewish history are recorded and

commemorated, their dates of birth are mostly unknown.” (Tauber)

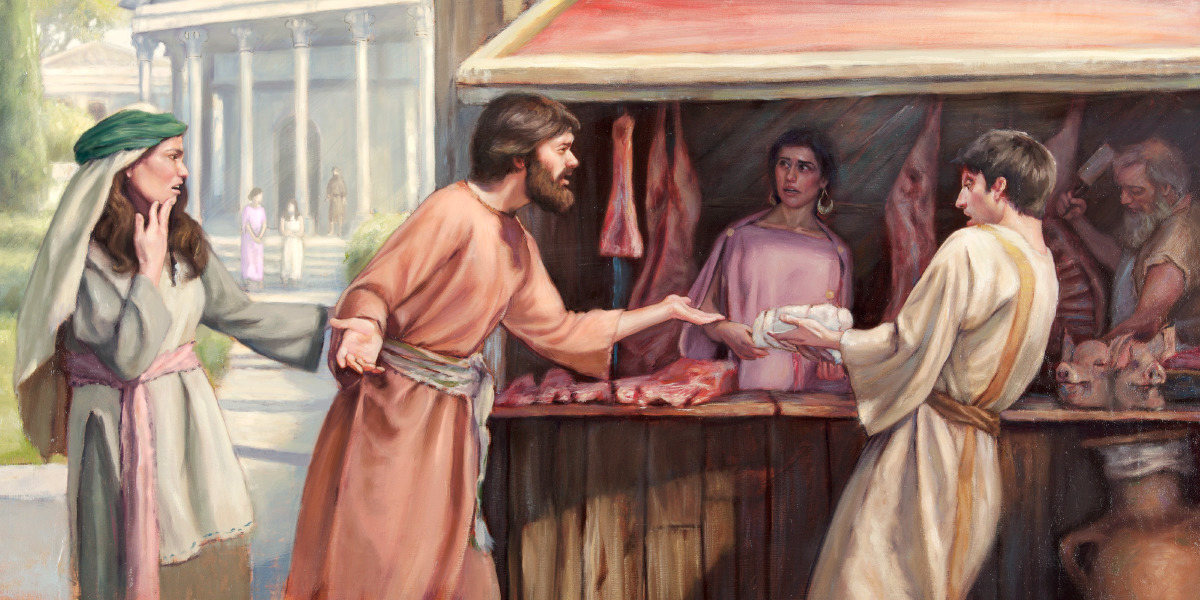

It is possible, as Tyler Rosenquist suggests, that they were looking for an alternative to the Caesar’s Birthday, a holy day

where no work was to be done and public prayers were made to Vesta and

sacrifices made to the Emperor. An inscription from Halicarnassus from the time

of Caesar Augustus is quite telling:

Providence has sent Augustus as a saviour for us… to make war to cease, and to create order everywhere… when he was made manifest, [Caesar] has fulfilled all the hopes of earlier times… and the birthday of the god [Augustus] was the beginning for the world of the good news (euaggelion [Gospel]) that has come to men through him” (in Thompson, p 62n24).

The authors of the New Testament indeed took back this language to describe Jesus, the one who alone rightly deserves these descriptions. But why wait until the late second century to take on the birthday celebration? Quite

possibly, because the number of Roman followers was growing, they were looking

for a way to honour the true and living saviour of the world, the true manifestation of the true God, in a culturally meaningful way. This could

have been subversive as an outright rejection and rebellion against the

Imperial cult, or as a way to appear acceptable during a time of growing persecution,

or as a way of contextualising mission. And all three could have been going on. History is quite complicated and things typically have multiple causes, so this is perhaps only one part of many to the story.

By the late second century, in the fallout of

the Bar Kochba revolt, the ‘Gentiles’ had significantly distanced themselves

from ‘the Jews’, disdaining anything that looks Jewish because of an anger

towards them rooted in a blame for increased persecution. Thus, we find Early

Church Fathers in this period writing things like:

Now, then, incline thine ear to me, and hear my words, and give heed, thou Jew. Many a time dost thou boast thyself, in that thou didst condemn Jesus of Nazareth to death, and didst give Him vinegar and gall to drink; and thou dost vaunt thyself because of this. (Hippolytus. Against Jews. 1).

There was also a wanting to distinguish themselves from

the Jews in they eyes of the Romans. Therefore, observing things like food laws and feast days were

condemned. Consequently, we find Justin Martyr writing things like:

For we too would observe the fleshly circumcision, and the Sabbaths, and in short all the feasts, if we did not know for what reason they were enjoined you,--namely, on account of your transgressions and the hardness of your hearts. (Trypho. 18)

And so, with a desire to celebrate the works of God but

no precedent on how to do so because they had cut themselves off from their

Hebraic heritage, the early Church invented Christmas. And eventually by the end

of the fourth century, Rome would outlaw what they defined as ‘Judaizing’ with

threat of excommunication, declaring Easter and Christmas as the only

legitimate Festivals. Perhaps this, more than supposed link to paganism should

be the cause of questioning Christmas. As Tyler Rosenquist reflects:

To me, knowing the history of the fourth century CE – that Rome forcibly legislated the removal of Christians out of the synagogues and Torah keepers out of the assemblies of Messiah – Christians celebrating Christmas and Easter seem very much like children celebrating the consequences of having a broken home. Without the Christians, the Jews lost their Messiah and without the Jews, the Christians lost their inheritance. It’s like a child celebrating the absence of a parent who wasn’t even a bad parent. Christmas and Easter happened because of a broken home, and that grieves me – it doesn’t make me want to celebrate. At one point all believers in Yeshua were called Nazarene Jews, for hundreds of years – Rome robbed us of a stable home life.

Not only does secular society investing so much into

Christmas baffle me, but seeing how much energy Christians put into a man-made

tradition does too. Although certain methods of celebrating Christmas could

arguably be unbiblical, the concept of Christmas is merely extra-biblical. And

celebrating the birth of Christ is good and worthy point of thanksgiving, but this is

where the inconsistency comes in. Some would argue, ‘I don’t need a Sabbath, I

can Sabbath any day.’ Yet, you won’t find them saying ‘I don’t need Christmas,

I can celebrate the birth of Jesus any day.’ The one, commanded in scripture is

minimised, while the man-made tradition is elevated. Does this sound familiar?

Is this not what Jesus rebuked the Pharisees for in Mark 7? “You have a fine

way of rejecting the commandment of God in order to establish your tradition!”

(Mark 7:9).

Is there anything wrong with traditions? No. Note that in

Mark 7 Jesus had washed his hands prior to eating. It’s when traditions supersede

Scripture that they become a problem, and it for this that Jesus often rebuked

them.

The early church did not need to invent new holidays, God

in His word had already provided His people with 7 feast days to celebrate, all

reflecting the person and work of Christ, thus making them worthy of Christian

observance and celebration. But because of their anti-semitism, the ‘Gentile

church’ turned their back on ‘Jewish’ things, thus abolishing the instructions

of God.

Now you may be thinking:

“Didn’t Paul say the feast days were done away with? In Colossians 2:16-17 he wrote: Therefore let no one pass judgment on you in questions of food and drink, or with regard to a festival or a new moon or a Sabbath. These are a shadow of the things to come, but the substance belongs to Christ.”

Yes, Paul wrote that, but he didn’t mean that. There are

two things about this passage that will help us understand what Paul is saying.

First, is that this passage says that it is wrong to judge, think less of, condemn

(kreno, Jn 3:17-18), and disqualify Christians

from the faith with the feast days as a measure. So this should give us perspective

on how Paul is defining the importance of the feast days, i.e. they aren’t

salvation critical. The second thing, however, reveals that Paul was not

talking to those who reject the feast days. Looking at the broader context,

note that Paul is warning his readers not to allow someone to take them “captive

by philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, according to the

elemental spirits of the world, and not according to Christ… These have indeed

an appearance of wisdom in promoting self-made religion…” (Col 2:8, 23). Now

the feast days are not ‘Jewish’, they are God’s feast days: “These are the

appointed feasts of the Lord that you shall proclaim as holy convocations; they

are my appointed feasts” (Lev 23:2). They are among His commandments and

statutes. If Paul is rebuking people for insisting on observing the Lord’s

feast days, then he is describing the commandments of God: empty, human tradition,

having the appearance of wisdom, and

self-made religion. Moreover, he is equating God with the ‘elemental spirits of

the world.’ Note too that these false teachers are insisting on “asceticism and

worship of angels, going on in detail about visions, puffed up without reason

by his sensuous mind… and severity to the body” as a way to overcome our sinful

nature and evil spirits (Col 2:8, 14, 18, 23). So Paul is in fact rebuking

false teachers for condemning Christians either because they were keeping the

feasts, or the manner in which they kept them. Insisting on aestheticism could

mean that celebrating anything was wrong, or perhaps the feasting and revelry of

the feasts should be exchanged for fasting. Thus, Paul is saying:

“Therefore let no one pass judgement on you because you keep the feasts or the way you keep the feasts. Why? For one, celebrating doesn’t promote sin. And secondly, because they are all about Jesus. So, of course you should celebrate them. And they haven’t passed away yet because they are ‘a shadow of the things to come’ [fut. Tense].”

So no, the feast days have not been done away with. Why

would our creator take away occasions for celebrating? Yet, because of the

inherited thinking from the likes of Justin Martyr, the church sees them as

something that needed to be done away with at the cross. And because of the

inherited interpretation of Colossians 2, most look upon them indifferently.

As I spoke about here and here God has already given us a perfect opportunity to celebrate the birth of Jesus:

the Feast of Tabernacles. Not only is it a highly probable date for Jesus’

birth, but it is a week of celebrations designed to help God’s people remember

that He dwells among them. A time to reflect on Immanuel. If people want to

celebrate Christmas, then that’s okay. There is nothing wrong with traditions.

There’s nothing in scripture explicitly forbidding it, nor for celebrating it more than once. Scripture doesn’t give a

date for the event, so we should not be dogmatic about when we celebrate it. But it is

important that we keep Christmas in correct perspective: it was a tradition

established to replace the days of celebration given by God in scripture, because the early church needed an outlet to honour their true saviour. Let’s give

both tradition and scripture the attention and energy they deserve.

Thompson, Alan J. One Lord, One People the Unity of the Church in Acts in Its Literary Setting / Alan J. Thompson. Library of New Testament Studies ; 359. London: T & T Clark, 2008.